Bones go through a continual process of remodeling throughout one’s lifetime. Getting enough material to continually rebuild bone is the key to strong, healthy bones and low risks of bone fractures.

There are many components that go into making bone tissue, from organic collagen proteins known as ossein to inorganic components such as minerals. While the organic component consisting of collagen and other proteins makes bones flexible, the inorganic component consisting of minerals makes bones strong and rigid.

Bones act as a storage site for minerals and are actually a metabolically active tissue. That is, bones undergo a continual process of reconstruction and thus depend on the continuous availability of mineral material for the reconstruction.

The availability of mineral material can make the difference between good bone density and strong, healthy bones, and weak bones predisposed to deformities and fractures.

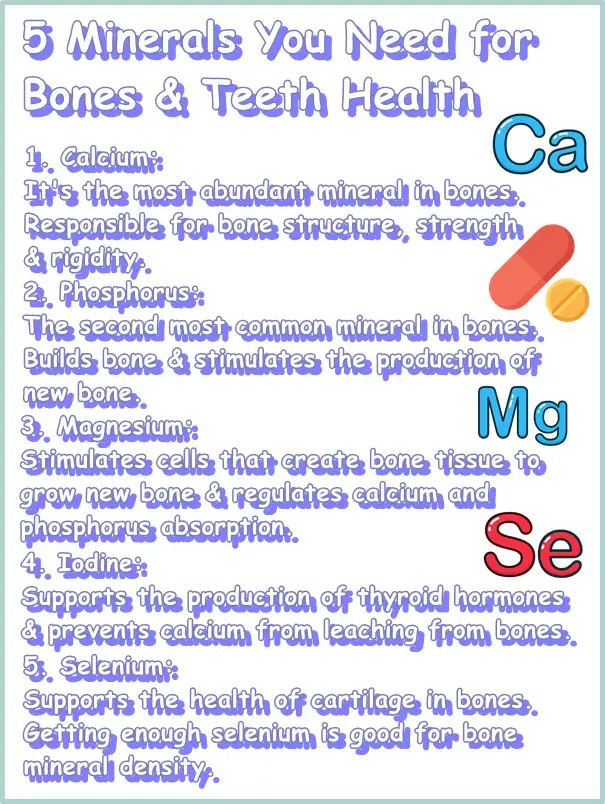

5 Minerals You Need for Strong Bones And Teeth

1) Calcium

Calcium is an inorganic mineral, an essential dietary nutrient and main contributor to bone tissue (source). Under normal conditions, almost all the calcium in the body at any given point in time is stored in bones (99%). Only about 1% of the calcium in the body circulates freely and is used for purposes other than building bones (e.g. cell signaling, transmission of nerve cell impulses, regulating muscle function for muscle contractions).

By now it’s common knowledge that you need calcium for your bones, and teeth. Half of all bone volume and close to two thirds of bone weight are represented by calcium which makes it the primary mineral in bone.

Calcium is also predominant in tooth enamel and dentin. The natural distribution of calcium in the body confirms the principal role it plays in maintaining bone mineral density, bone strength and bone health.

Studies confirm ‘a continual supply of calcium in the diet throughout life is essential’ (source) for maintaining good bone density, bone rigidity and bone strength. In the first decades of life, sufficient calcium is required for the normal development and mineralization of the skeleton, and achieving optimal bone mineral density with benefits for bone structure, strength and rigidity. Just as important, calcium is needed continually throughout one’s lifetime in sufficient amounts for maintaining bone metabolism as it undergoes a continuous process of remodeling.

2) Phosphorus

Phosphorus is revealed as a dietary mineral that heavily contributes to bone makeup, building and strengthening bone tissue. It is estimated that about 85% of all phosphorus found in the body at any given time is stored in bones. Phosphorus deficiency directly affects skeletal health and causes bone demineralization resulting in rickets and osteomalacia with side effects such as weak, frail or soft bones, associated bone deformities, and increased risks of fractures.

In addition to providing structure to bones and increasing bone strength as part of the inorganic component of bone tissue, phosphorus further benefits bone health via its regulatory functions. More exactly, phosphorus actively modulates bone growth, stimulating the production of new bone from bone-forming cells via a regulatory action. At the same time, it regulates bone resorption, the process of breaking down bone tissue, essentially contributing to life-long bone remodeling processes.

3) Magnesium

Bone is made up of around 70% inorganic tissue consisting of minerals, primarily calcium and phosphorus which occur in a complex that represents about 95% of all bone mineral composition. But other minerals also contribute to bone makeup and bone metabolism. One of these minerals is magnesium.

According to research, ‘magnesium is essential for bone development and mineralization’. For one, magnesium physically contributes to bone makeup, albeit to a lesser extent compared to calcium and phosphorus. It is estimated that about 60% of all the magnesium present in the body at any given time is found in bones.

More important, magnesium has a regulatory action on the activity of osteoblasts, cells that form new bone tissue, stimulating them to grow new bone, as per normal bone metabolism, and helps maintain normal bone homeostasis. Magnesium further supports the production of new bone tissue by regulating the activity of phosphorus-based enzymes (source).

While poorly represented in bone tissue composition, magnesium has a direct and meaningful impact on both calcium and phosphorus metabolism and, in adequate amounts, can exert a beneficial regulatory action that encourages bone mineralization and achieving optimal bone density for bone health.

Study results have identified magnesium as a modifier of bone fracture risks (source) and hypothesize that you can lower risks of bone fractures if you get enough magnesium daily in the diet. For example, ‘significantly higher bone mineral density of the hip and whole body (…) were noted in women with a higher daily magnesium intake’ as well as ‘higher total body bone mineral density in postmenopausal women’ (study).

However, both too much and too little magnesium can have a deleterious effect on bone metabolism and bone health, according to research. Magnesium deficiency, which is extremely common, and far more likely than excess intakes, causes poor bone mineral density, loss of bone mass and higher risks of bone fractures (source).

High levels of magnesium impair the activity of osteoblasts, bone-forming cells, affecting the production of new bone tissue and normal bone metabolism which could negatively impact bone health over time (source). Too much magnesium competes with calcium for absorption in bones, causing poor bone mineralization and increased risks of bone fractures long-term.

One way to bypass the issue of magnesium and calcium competing for absorption, in instances when supplementation with higher doses of both minerals is required, is to take the two separately, at different times of the day or at least 4 hours apart.

4) Iodine

Hormones are directly and meaningfully involved in all aspects of health, regulating everything from fertility and weight to sleep, mood, appetite and bone density and bone health. Hormones determine bone mineral density and influence the growth and maintenance of bones via various regulatory activities.

For example, thyroid calcitonin regulates calcium blood levels as well as phosphorus metabolism. Incidentally, calcium and phosphorus are the two main minerals that go into building bone tissue accounting for an estimated 95% of all inorganic bone tissue.

Calcitonin is a thyroid hormone produced naturally by the thyroid gland. Its role is to regulate calcium and phosphorus metabolism. Calcitonin is best known for lowering calcium levels in the blood and it does so by exerting an inhibitory effect on osteoclasts, bone cells that break down bone tissue.

When bone tissue is broken down, whether to initiate repairs in case of a fracture or as a normal part of natural bone metabolism (bones are in a continual process of remodeling), minerals from bone tissue such as calcium (phosphorus and others) are released into the bloodstream. Calcitonin inhibits the release of minerals from bones, contributing to maintaining good bone density and strong healthy bones.

However, when the thyroid gland is malfunctioning, regulatory processes such as these are impacted and, by extension, various aspects of health, in this case, normal bone metabolism and bone health. For example, an underactive thyroid does not produce enough thyroid hormones, including calcitonin. This means that calcitonin no longer stops bone remodeling as part of normal bone metabolism which causes minerals such as calcium to leach from bones resulting in poor bone density and poor bone health.

And one of the leading causes of hypothyroidism, or an underactive thyroid, is iodine deficiency which underlines the importance of dietary iodine for good bone density and bone health. The thyroid also regulates phosphorus metabolism via the kidneys which further emphasizes its role in maintaining good bone density and bone health.

The thyroid as an organ is heavily dependent on iodine for normal functioning. A iodine deficiency can severely impact thyroid health and the production of thyroid hormones which, in turn, affects bone health reducing bone mineral density which puts one at risk for bone fractures. Also see what vitamins you need for bone health.

5) Selenium

Getting sufficient selenium in the diet every day, enough to meet individual dietary requirements, can help with bone density and contribute to bone health long-term. For one, selenium is needed by the thyroid to stay healthy and produce sufficient thyroid hormones.

Thyroid hormones regulate various aspects of health, including the metabolism of the two main components of bone tissue: calcium and phosphorus. A selenium deficiency causes an underactive thyroid and an underactive thyroid leads to loss of bone mineral density and soft, weak bones predisposed to fractures.

Moreover, research provides evidence that ‘selenium deficiency has an impact on cartilage thereby having an indirect impact on bone’ health (source). Bone tissue is actually an amalgam of different types of tissue, including cartilage (and also bone marrow, blood vessels, nerves and more). Bone cartilage is dependent, among others, of sufficient dietary selenium for normal growth and development.

‘Animal studies suggest selenium deficiency results in cartilage defects’ which impacts various aspects of bone health, affecting normal growth and development, and even mobility. Side effects may include bone deformities, stunted growth and functional impairment.

Moreover, there is research that demonstrates that selenium status is positively associated with bone mineral density, independent of thyroid function (source), further underlining the benefits of adequate selenium intake for bone health.