With the recent E. coli outbreak being traced back to romaine lettuce and possibly several other related greens (once again), it’s high time there was an honest discussion about the hows and whys and all the important information that needs to be put out there in order for everyone to better understand what is going on and what means we have at our disposal to prevent, manage and treat E. coli infections, should they occur. From E. coli types and what they do to how E. coli gets into our food, particularly into lettuce, what symptoms to look out for, what side effects to expect and what to do about it, we’ll try to cover everything that’s important about the subject in a simple and hopefully, pertinent, discussion.

E. coli outbreak 2018

This year, there was yet another major E. coli outbreak in the US. The first cases were reported around mid-March and currently, there are reports of E. coli infections coming from over 30 states. The number of people sick with a pathogenic strain of E. coli is a little over 170. But because E. coli symptoms may take up to 3-4 weeks to manifest in some people, it is still possible for slightly more cases to be reported in the following days. Authorities have traced the infection back to contaminated romaine lettuce grown in Yuma, a city in Yuma county, Arizona. The contaminated lettuce is reported to have been distributed to restaurants and supermarkets all over the US via multiple distributors, which makes it almost impossible to learn at which point the contamination occurred and through which means. People have been advised to check the label of their romaine lettuce and salad mixes containing romaine lettuce for origin and avoid all products from the suspected region or whose origin cannot be identified.

What is E. coli? E. coli is short for Escherichia coli and is a gram-negative bacterium, shaped like a rod – a bacillus (read more about the Difference between Gram Negative and Gram Positive Bacteria). Not all E. coli bacteria produce infection and disease. There are strains of E. coli that are present naturally in the gastrointestinal system of humans and animals with warm blood without producing infection. Of those present naturally, some are commensal, meaning they feed by processing some of the things we eat, but don’t do anything else. Some E. coli are beneficial bacteria that help synthesize vitamin K2 for us. And then there are pathogenic strains of E. coli which cause infection and disease.

E. coli infection

E. coli infections are produced by a small number of pathogenic Escherichia coli strains (a strain is basically a variation, in this case a variation of the bacterium). Disease occurs in the form or diarrhea, with or without fever. Pathogenic E. coli strains can cause bacterial gastroenteritis (stomach bug), enterocolitis (inflammation of the small intestine and colon), colitis, urinary tract infections and, in rare cases, hemolytic-uremic syndrome that can potentially lead to kidney failure.

E. coli symptoms

Signs and symptoms of an E. coli infection may be different, depending on which strain of the bacterium is causing the infection. Overall, look out for:

1) Diarrhea (loose watery stools), with or without blood (diarrhea with blood is a sign of a severe form and requires immediate medical attention).

2) High fever or no fever (some strains don’t cause fever).

3) Painful abdominal cramps, usually caused by the diarrhea.

4) Nausea and vomiting.

A rare complication caused by a specific strain of E. coli is hemolytic-uremic syndrome, which primarily affects small children. Hemolytic uremic syndrome is caused by a strain of E. coli that produces a toxin that causes the destruction of red blood cells, causing anemia as a result. This also overloads the kidneys and may ultimately lead to kidney failure. Kidney failure then causes high blood pressure and edema with swelling of the legs, arms, eyelids etc. Another complication of hemolytic uremic syndrome is low platelet count, or low levels of thrombocytes (cell fragments in the blood that initiate blood clots to prevent bleeding). Low urine output and blood in urine are other symptoms (read more about Urine Colors and What They Mean). The condition is life-threatening because it can quickly build up to severe dehydration, neurological damage, permanent kidney damage, liver damage, multiple organ failure and coma. Hemolytic uremic syndrome is a medical emergency and requires immediate medical intervention.

How does E. coli spread?

Pathogenic E. coli spreads through ingestion of stool matter. The bacteria are shed in stools and often continue to replicate in the stools for up to three days. Direct contact causes a person to pick up the bacteria and transmit it to other objects and people, leading to the spread of the infection. Both humans and domestic and wild animals (cows, pigs, deer) can be carriers of the bacteria and transmit the infection further.

How does E. coli infect humans?

Pathogenic E. coli bacteria are acquired via contaminated food, water or contact with objects contaminated with stool matter of infected people or animals. Here are some examples of how E. coli is transmitted to people:

1) Drinking contaminated water or eating contaminated food.

2) Touching contaminated objects and not washing hands before eating or preparing food or touching the contaminated objects while eating or preparing food (example: picking up the phone to answer a call while handling food).

3) Contact with contaminated objects, from public places or from your own home (door knobs, tables, pens, cell phones, underclothes, dirty diapers etc.) and not washing hands afterwards, especially before eating. Swimming pools are also a possible source of contamination.

4) Not washing hands after using the bathroom, changing diapers, touching underclothes etc.

5) Improper handling of food at home or at eating establishments: not washing certain foods well; handling contaminated raw chicken or other raw meat, then touching fruits or vegetables or other foods you will eat raw; preparing a salad on the same wooden board you used for raw meat or using the same knife for meat and vegetables and fruit etc.

6) Sharing personal objects (toothbrush, towels), food or tableware (fork, spoon, plate, glass) with someone who exhibits symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and especially diarrhea.

7) For small children, being in day care, kindergarten or school ups infection risks. Presence of sick children at the playground rises the chances of the child transmitting the infection to the others. If a member of the household has infectious diarrhea, this increases the chances of the infectious agent spreading to the other members of the family.

How does E. coli get into food?

The most likely causes include:

1) Lack of hygiene and improper handling. Foods may be contaminated during harvesting, processing or delivery by the people handling them, if these people are sick with infectious diarrhea or come into contact with contaminated stools and don’t uphold a very strict hygiene (wash their hands, wear gloves).

2) Use of untreated sewage water. A lot of foods may be contaminated as a result of the use of untreated waste water for irrigation. Farms may use sewage water directly on crops, increasing the risk of contamination with bacteria and other pathogens from human waste. This is the case for foods like lettuce, spinach and other leafy vegetables or any crop with edible leaves, stems, fruits, flowers or seeds growing close to the ground (the closer to the ground, the more likely contact with untreated contaminated water).

3) Contamination from wild and domestic animals. For example, apples grown in orchards in highlands may be accessed by wild animals like deer or cattle or sheep which may carry pathogenic bacteria. Any fruit fallen on the ground may come into contact with contaminated stool matter. Unless used in pasteurized products (pasteurized apple juice or applesauce) or if eaten unwashed, they represent a plausible source of infection. Feral pigs and other wild animals may contaminate various crops.

4) Other ways E. coli gets into food. Organic fertilizers represent a source of contamination with bacteria like E. coli. Cattle may also be infected and produce contaminated milk which can represent a source of infection if not pasteurized. Beef, chicken and other meats may be contaminated and improper handling can further lead to the spread of the bacteria (example: using the same cutting board or kitchen utensils for raw meat and foods you eat raw, like salad vegetables or fruits).

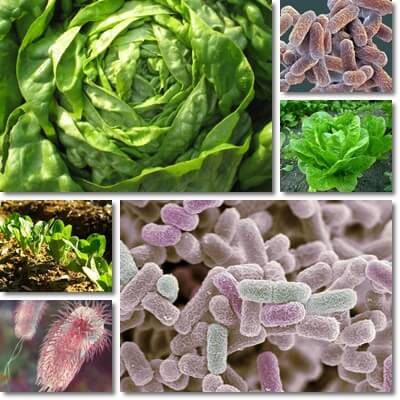

How does E. coli infect romaine lettuce?

This year’s E. coli situation was caused by contaminated romaine lettuce. Since the contaminated lettuce is believed to have come from a single growing area, it is possible to have been irrigated with untreated or improperly treated wastewater or grey-water. It is possible the lettuce was irrigated too close to its harvesting which would have allowed bacteria to survive this well seen the range of the epidemic.

For leaf vegetables like lettuce or romaine lettuce, spinach, rocket salad (arugula) how E. coli spreads this massively is also likely through use of contaminated organic manure, in addition to use of untreated sewage water for irrigation. Errors in handling cannot be excluded either. Leafy vegetables in general are often also more difficult to wash and commonly eaten raw, which also adds to the likelihood of them causing infectious disease.

How long for E. coli infection symptoms to show up?

The incubation period for pathogenic E. coli bacteria varies greatly, but the average is 3-5 days until symptoms manifest. In some cases, symptoms may show up in as little 1 day following exposure to the bacteria (ingestion) or up to 10 days. Timeline is similar to gastroenteritis (read more about Gastroenteritis: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment). Complications such as hemolytic uremic syndrome may occur 7-10 days after the first symptoms.

How long does an E. coli infection last?

In healthy adults, given proper symptoms management, the infection may last anywhere from 3 to 5 days. If more severe, the infection may take 7-10 days to clear.

How to treat E. coli infections?

E. coli treatment consists mainly of symptoms management. Because of the diarrhea and vomiting, the greatest risk is dehydration, so the biggest focus is managing it. Drinking plenty of liquids (water, sweetened tea, sports drinks containing electrolytes, rehydration solutions) helps maintain fluid balance and aids in a faster recovery. Rest and proper hygiene are also essential.

It is also important to see your doctor if you experience symptoms like diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. The doctor will usually assess the evolution of your symptoms and perform tests and, based on results, may or may not prescribe antibiotics. If your doctor prescribes antibiotics, take them as recommended. If nausea and vomiting are severe and continue for more than 1-2 days, your doctor may recommend antiemetics to stop the vomiting and prevent dehydration. Antidiarrhea medication is usually not given because the body must be allowed to eliminate the bacteria.

If you experience complications such as blood in stools (diarrhea with blood) or blood in urine, low urine output (lack of urination), dizziness, confusion know that they are a medical emergency and you need to see a doctor as soon as possible. Children, pregnant women, the elderly and adults with complications as well as anyone with an existing chronic condition must see a doctor for adequate treatment.

Prevention consists of excellent hygiene and includes:

1) Wash hands well with soap and water before and after eating, before and after handling different foods (example: wash hands after preparing raw meat, before you prepare fruits or vegetables or other foods).

2) Wash and sanitize cutting boards after preparing meat and use different ones for cheeses, fruits and vegetables you eat raw.

3) If a certain food is suspected of contamination (lettuce, spinach, arugula, cucumbers), avoid eating it raw until all potentially contaminated products containing it are recalled.

4) Wash vegetables and fruits very well in plenty of water.

5) Cook foods well, especially meat. Choose pasteurized fruit and vegetable juices, milk and dairy.

6) Store meat separately from eggs, dairy, vegetables, fruits in the refrigerator.

7) Practice good hygiene overall. Example: wash hands well before feeding babies or toddlers or preparing their food, after changing diapers, using the toilet or helping a household or family member with infectious diarrhea. Disinfect surfaces you handle or prepare food on, food preparation utensils and any possible source of bacteria transmission, avoid touching your mouth with your hand, wash underclothes at high temperatures.